For coaches, effectively assessing a client’s movement quality is the essential first step. The benefit of functional movement and performance training lies in its ability to improve daily life activities, prevent injuries, and enhance overall performance, providing practical advantages that extend beyond the gym. Evaluating functional capacity moves beyond simple strength or cardiovascular metrics, such as cardiovascular fitness. It focuses on how efficiently and safely an athlete performs real-world, dynamic tasks. A successful program requires defining functional ability and capacity early to identify and correct limiting factors. This comprehensive guide, combined with the right personal trainer software, will equip coaches with the necessary principles and practical tests to manage client data effectively. Mastering the evaluation of functional movement and performance training guarantees safer, faster, and more sustainable results.

Defining Functional Ability and Capacity

The terms functional ability and capacity are often used interchangeably, but they represent distinct concepts in athlete evaluation. Understanding this distinction is key to choosing appropriate testing and corrective strategies. Functional capacity refers to the total potential output of the athlete’s system. It is the ceiling of what the athlete can physically achieve.

Assessments of functional ability and capacity should be tailored to individual fitness levels to ensure that testing and corrective strategies are appropriate for each person's unique needs and goals.

Functional Fitness and Motion in Sports

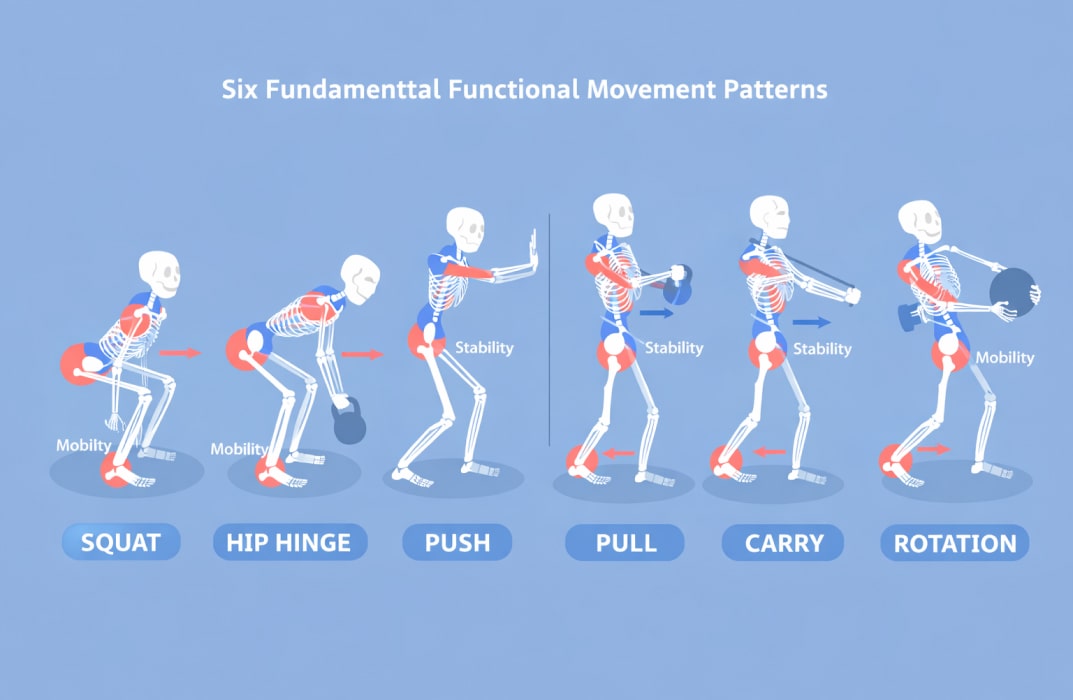

Functional fitness and motion describe the body’s ability to move efficiently through fundamental patterns. These patterns are designed to reflect the way the body naturally moves in daily life. These patterns include squatting, hinging, pushing, pulling, rotating, and carrying. In sports, functional movement must be highly efficient, resilient, and pain-free. The assessment focuses on identifying limitations in joint range of motion and muscle activation during these movements. A high level of functional ability means the athlete can perform the core movements effectively, regardless of the load.

The Continuum of Ability to Capacity

Functional ability is a prerequisite for functional capacity. Ability relates to the quality of the movement pattern itself, such as performing a perfect, unweighted deep squat. Capacity relates to the quantity of work the body can perform using that movement. This includes how much weight can be lifted or how many repetitions can be achieved with that perfect form. Endurance is also a critical aspect of capacity, reflecting the ability to sustain performance over time. Coaches must prioritize fixing the ability (movement quality) before pushing the capacity (load or volume). Compromising this continuum leads directly to injury risk.

Also Read: The Specificity Principle Improves Targeted Fitness Results

Differentiating Static vs. Dynamic Functional Movement Tests

Effective evaluation of functional capacity requires differentiating between two primary categories of assessment. Static tests assess the body’s structure and alignment while the athlete is at rest. Dynamic tests assess the body’s control and efficiency while the athlete is actively moving. These tests provide insight into how the nervous system coordinates movement for optimal performance. Coaches must utilize both to gain a complete picture of the athlete’s functional ability. Relying on only one type of test creates blind spots in the training program. The predictive value of dynamic tests for injury risk is generally higher than that of static tests. This is because most sports and daily activities require coordinated, multi-planar movement, not static holding. Therefore, dynamic screens offer a better insight into performance readiness.

Static Postural Assessment and Limits

Static postural assessment involves observing the athlete’s body alignment in standing, sitting, or lying positions. This test identifies structural asymmetries and potential muscle length discrepancies. For instance, observing one shoulder lower than the other suggests an imbalance in the upper trapezius or levator scapulae. Static limits refer to the non-moving, maximal range of motion achievable at a joint. Achieving a full range of motion is essential for optimal joint health and function. A simple test, like the sit-and-reach, determines the static limit of hamstring flexibility. The main limitation is that static screens do not predict actual functional movement quality under load.

Dynamic Stability and Range of Motion Tests

Dynamic tests assess the body’s ability to maintain control and stability throughout a movement pattern. Each test should begin from a standardized starting position to ensure reliable results. These tests are far more indicative of functional ability in real-world sports and activities. Dynamic stability refers to the control achieved during motion, particularly in the frontal and transverse planes. For example, the Single-Leg Squat assesses the dynamic stability of the hip and knee. The dynamic range of motion tests how far an athlete can move a joint while actively maintaining control. Assessing rotational stability during movements like the single-leg hop is vital. Lack of rotational control is often a precursor to ankle or knee ligament issues. These dynamic tests are crucial for identifying compensation patterns that mask underlying mobility limitations.

Criteria for Functional Movement Assessment

Evaluating functional capacity is more than just observing movement; it requires a systematic set of criteria to identify the root cause of movement dysfunction. Unlike assessments that focus on the performance of one muscle, functional movement assessments evaluate how multiple muscles work together in coordinated patterns. Coaches must assess not just what the athlete does, but why they are compensating. These criteria define the standards for optimal functional movement and performance training. Adherence to these criteria ensures the assessments are reliable and actionable.

Mobility vs. Stability Screens

A fundamental principle in assessing functional ability is determining whether the movement restriction stems from a lack of mobility or a lack of stability.

- Mobility refers to the required range of motion at a joint, often checked through passive or active range tests. For instance, testing ankle dorsiflexion against a wall determines the necessary mobility for squat depth. The elbow joint is another common site for mobility assessment, especially in pushing or pulling movements.

- Stability refers to the ability to control the available range of motion. An athlete might have excellent hip mobility, but lack the core stability to control the spine during a heavy deadlift. The criterion for a successful screen is identifying which component mobility or stability is the primary limiting factor.

Identifying Compensation Patterns

Compensation is the body’s natural strategy to accomplish a movement when the optimal path is unavailable due to pain, mobility restriction, or weakness. Compensation patterns are the primary indicator of poor functional movement. For example, when an athlete lacks ankle dorsiflexion during a squat, they compensate by lifting their heels or excessive forward trunk lean. The assessment criteria must focus on noticing these deviations from ideal movement. Failure to address these patterns perpetuates faulty mechanics and increases the risk of injury. The goal is to correct the compensation by fixing the underlying limitation in functional ability. For instance, instructing an athlete to slowly lower their body during a movement, such as a leg raise, can reveal or help correct compensation patterns by emphasizing control and proper muscle engagement.

Also Read: Sports-specific training boosts performance and prevents injury.

Essential Tests for Functional Movement and Performance Training

Coaches utilize specific, standardized tests within their fitness trainer software to objectively measure an athlete’s functional ability and identify subtle weaknesses. These essential screens require minimal equipment and provide maximum insight into the athlete’s movement quality. Some of these tests are designed to assess upper-body strength in addition to movement quality. Integrating these tests is fundamental to effective functional movement and performance training. They offer a concrete, measurable baseline for future progress tracking.

1. Lower Body Bilateral (Symmetrical) Screens

These tests evaluate the body’s ability to handle load and motion symmetrically.

- The Deep Squat Test: This is a foundational test that assesses bilateral, symmetrical, and simultaneous mobility of the hips, knees, and ankles. It immediately reveals an athlete’s ability to maintain a neutral spine while achieving a full, safe depth. Proper form requires keeping the knees bent and aligned with the toes throughout the movement. Failure to perform a good, deep squat often indicates mobility restrictions in the ankle (dorsiflexion) or tightness in the hip flexors.

- The Hurdle Step Test: This screen assesses hip stability and mobility in the sagittal plane while challenging the single-leg stance of the supporting leg. It requires the athlete to step over a hurdle while maintaining proper hip and core alignment. This test is crucial for assessing unilateral leg stability and coordination during cyclical activities like running.

2. Lower Body Unilateral (Stability) Screens

These tests challenge the body’s stabilizing muscles and neuromuscular control on one side.

- The Single-Leg Stance and Balance Test: This is a critical screen for dynamic stability and neuromuscular control. The athlete is asked to stand on one leg for a specified time. During the test, the athlete may be asked to balance on the right foot or left foot, and the position of the right heel and left heel is important for maintaining stability and proper form. Any excessive wobbling, knee valgus (caving in), or noticeable hip drop indicates poor intrinsic stability of the foot and hip musculature. Poor performance here suggests a higher risk for ankle sprains and knee injuries during running and cutting movements.

3. Upper Body and Trunk Mobility Screens

These tests assess the coordinated movement between the thoracic spine and the shoulder girdle. Some trunk mobility screens may also involve coordinated movement of the right knee, left knee, or right leg to assess full-body integration.

- The Overhead Reach Test: This screen is used to evaluate shoulder girdle mobility and thoracic spine extension. The athlete attempts to reach both arms overhead while keeping the elbows straight and the lumbar spine neutral. The test can also be performed with either the right or left arm to assess unilateral mobility. Excessive arching of the lower back indicates a lack of thoracic extension or tightness in the latissimus dorsi. Optimal performance demonstrates good scapular rhythm and the necessary range for safe overhead activities.

The Role of Core Stability in Functional Ability

The core is fundamentally the engine room and the critical link between the upper and lower extremities. It is central to defining and maximizing functional ability and is the primary stabilizing force for the entire body. Building core strength is essential for stability, injury prevention, and overall fitness, making it a foundational aspect of functional movement and performance training. Poor core stability significantly limits both movement quality and maximal power output. Without a stiff, controlled core, the kinetic energy generated by the large muscles of the legs and hips cannot be efficiently transferred to the upper body, resulting in lost force. Assessing the core should focus less on traditional flexion movements like sit-ups, which train mobility, and more on its crucial role in preventing unwanted motion.

Assessing Anti-Rotation and Anti-Extension

True functional movement and performance training requires the core to resist external forces, thereby acting as a powerful brake, rather than primarily initiating movement. Coaches must assess the core’s ability to resist rotation, extension, and lateral flexion forces.

- Anti-Rotation: Tests like the Pallof Press and Rotational Chops assess the core’s ability to prevent the trunk from twisting or spiraling under lateral or asymmetrical load. This is a vital skill for athletes involved in asymmetrical sports like golf, baseball, hockey, or any activity involving sudden, powerful changes in direction.

- Anti-Extension: Tests like the Plank, Abdominal Rollouts, or the Body Saw assess the core’s ability to prevent the lower back from arching or moving into excessive extension. After each repetition, athletes should slowly return to the starting position to maintain control and prevent injury. This is a crucial skill for maintaining spinal integrity and preventing painful hyperextension during heavy overhead presses, military presses, or dynamic carrying tasks.

Connecting Core Stiffness to Limb Power

Core stiffness, or spinal rigidity, is directly proportional to power generation in the limbs. This concept is sometimes referred to as "Proximal Stability for Distal Mobility". When the core is stiff, it provides a stable base (a rigid lever) from which the hips and shoulders can generate maximum, explosive force. Conversely, a soft, yielding, or "wobbly" core will leak kinetic energy during movement. For example, during a powerful athletic throw, kick, or maximal vertical jump, a weak core will lead to energy dissipation through a collapsed or hyper-extended trunk. This reduces the velocity and force expressed at the hand or foot. Therefore, improving functional capacity often begins by enhancing the core’s ability to stabilize the spine against external forces, ensuring efficient transfer of force throughout the body.

Importance of Grip Strength in Functional Performance

Grip strength is a foundational element of functional performance, directly influencing how effectively we navigate everyday life and real-world activities. Whether it’s carrying groceries, climbing stairs, or lifting heavy weights, a strong grip is essential for maintaining independence and performing daily tasks with confidence. In the context of functional fitness training, grip strength is more than just a measure of hand power; it’s a reflection of overall functional ability, core stability, and the body’s capacity to move efficiently through multiple planes of motion.

Functional training programs often incorporate exercises that challenge grip strength in ways that mimic real-life activities. For example, carrying exercises, such as farmer’s walks or suitcase carries, not only build functional strength in the hands and forearms but also engage the core and improve balance and coordination. Even movements like jump squats, where the knees are bent and the body is lowered into a powerful position, require grip strength to stabilize weights and maintain control throughout the movement. Upper body exercises, such as bicep curls or pull-ups, further reinforce the importance of grip strength in supporting overall muscle mass and functional workouts.

The significance of grip strength becomes even more pronounced with age. Older adults often experience age-related changes, including decreased muscle mass and reduced strength, which can impact their ability to perform everyday tasks and increase the risk of falls. By incorporating grip-strengthening exercises into regular strength training and functional fitness routines, older adults can counteract these changes, enhance their functional ability, and support fall prevention. This proactive approach not only promotes a healthy life but also helps maintain a capable body well into later years.

Training sessions designed to improve grip strength can include a variety of targeted exercises. Wrist curls and extensions, towel or rope holds, and dead hangs are effective ways to build strength in the forearm, wrist, and hand. Additionally, integrating grip challenges into core-focused movements, such as planks or side planks while holding onto weights, further develops both grip and core stability. The key is to start with manageable loads and gradually increase intensity, allowing the muscles to adapt and build strength safely over time.

Incorporating grip strength training into workout routines benefits individuals of all fitness levels. It enhances overall fitness, mobility, and coordination, making daily life tasks easier and reducing the risk of overuse injuries. By focusing on grip strength as part of a comprehensive functional training program, individuals can improve their performance in real-life activities, support healthy aging, and enjoy greater independence and well-being.

In summary, grip strength is a vital component of functional fitness and should not be overlooked in any training program. By prioritizing grip strength alongside core stability, mobility, and balance, coaches and individuals alike can build a more resilient, functional, and capable body ready to meet the demands of everyday life and beyond.

Also Read: Post-Workout Recovery & Mobility Routines for Clients

Practical Application of Functional Ability Results

The goal of evaluating functional capacity is not merely to identify weaknesses but to create targeted solutions that drive progress. Assessment results must directly inform the program design, shifting the focus from general strength training to highly specific corrective work. This intentional bridge between screening and prescription is the hallmark of effective functional movement and performance training. Coaches should view the initial assessment as the diagnostic phase, where limitations are clearly mapped out. The program then becomes the therapeutic phase, prioritizing the restoration of foundational movement patterns. This systematic approach ensures that strength is built upon a stable and mobile base.

Designing Corrective Strategies

Corrective strategies are exercises specifically designed to eliminate the mobility restrictions or stability deficits identified during the screens. The hierarchy for correction dictates that mobility should be addressed before stability. A joint must have the required range of motion before the body can learn to control it.

- Mobility Correction: If the Deep Squat test revealed poor ankle dorsiflexion, the corrective strategy would involve targeted ankle mobilization drills before squatting.

- Stability Correction: If the Single-Leg Stance revealed hip instability (knee valgus), the corrective strategy would emphasize gluteal activation exercises like clam shells or band walks. The prescription must be specific: if the fault is mobility, stretch it; if the fault is stability, activate and strengthen it. The principle of 'proximal stiffness for distal mobility' guides the choice, often starting with core and hip stability. This focused work enhances the overall functional ability of the athlete.

Integrating Correctives into Warm-ups

The most effective way to ensure client adherence to corrective work is to integrate it into the training session seamlessly. Corrective exercises should form the initial part of the warm-up, often called the "movement prep" phase. The movement prep serves to activate weak or inhibited muscles and mobilize tight joints, preparing the body for the heavy lifting to come. This saves time and ensures the client achieves optimal movement patterns under supervision. This integration ensures that the client's optimal functional fitness and motion are achieved before load is applied. By placing the correctives here, coaches address the fundamental issues immediately, improving the quality of every repetition that follows.

Furthermore, coaches should retest the specific failed movement pattern every 4-6 weeks. Retesting provides objective feedback on the effectiveness of the corrective strategy and guides the evolution of the training program. If the ability has improved, the coach can safely increase the capacity.

Linking Functional Movement to Performance

The ultimate goal of assessing and improving functional ability is to enhance athletic performance, increase maximal output, and ensure long-term longevity. There is a direct and measurable link between efficient functional fitness and motion and the expression of speed, power, and maximal strength. Coaches must understand that movement quality acts as the stable foundation upon which high-level athletic traits are built. Poor movement acts as a critical bottleneck, creating points of energy leakage that severely limit the athlete's potential ceiling.

Assessing Power and Speed in Functional Context

Once foundational functional capacity is established (meaning the movement is safe and controlled), coaches can test the functional transfer of these improvements to speed and power. This involves using dynamic tests that closely mimic sporting movements.

- Vertical Jump Example: When an athlete with poor ankle dorsiflexion performs a maximal vertical jump, they will be forced to excessively lean their trunk forward. This forward lean compromises the powerful vertical extension of the hip, resulting in lost jumping height. The functional deficit (ankle mobility) directly limits the performance metric (vertical power).

- Throwing Example: For a baseball pitcher or a thrower, a lack of core anti-rotation stability means that the rotational energy generated by the hips cannot be efficiently transferred to the shoulder and arm. The kinetic energy "leaks" through the unstable lower back, reducing throwing velocity and increasing strain on the shoulder joint. Functional movement and performance training requires transferring that corrected, conscious control into unconscious speed.

Injury Mitigation through Assessment

One of the most valuable and often underappreciated aspects of functional assessment is its powerful role in injury mitigation. Identifying and correcting movement asymmetries, such as a large difference in single-leg hop distance or a noticeable side difference in balance time, can drastically reduce the risk of non-contact injuries. An imbalanced functional ability means one side of the body is forced to take on a disproportionate amount of physical stress during activities. By using the assessment to expose these weak links, such as a hip that drops excessively during running, coaches can target the program to build resilience and distribute stress evenly. This proactive approach saves the athlete from lost training time and ensures long-term commitment to functional fitness and motion.

Technology and Data Capture in Functional Fitness and Motion

Modern functional movement and performance training increasingly relies on technology to enhance the accuracy and objectivity of movement assessment. While traditional visual assessment is crucial, technology provides quantifiable data that coaches can use for precise tracking and client feedback. Leveraging these tools helps coaches move beyond subjective observations of functional ability.

Using Video Analysis for Movement Feedback

Video recording and slow-motion playback are accessible and powerful tools for evaluating functional capacity. Recording an athlete performing a squat or a jump allows the coach to analyze mechanics frame-by-frame, pinpointing the exact moment a compensation pattern occurs. This visual evidence is invaluable for client education. By seeing their own movement flaws, clients can more effectively understand and internalize the corrective cues given by the coach. Simple smartphone applications offer grid overlays and drawing tools that enhance the precision of the functional fitness and motion feedback.

Force Plates and Motion Capture Benefits

For advanced functional movement and performance training, specialized technology offers detailed, objective metrics.

- Force Plates: These measure the ground reaction forces during movements like jumping, landing, or single-leg stances. They provide quantifiable data on left-right limb asymmetries, power output, and the force absorption during landing. These numerical metrics define functional deficits with precision.

- Motion Capture Systems (3D): These systems use markers placed on the body to track joint angles and velocities in three dimensions. They offer the most accurate assessment of how the body moves in space. This data helps precisely define functional ability related to joint loading and efficiency. While expensive, these tools offer unmatched objective insight.

Simplify Your Assessment and Planning

Mastering the evaluation of functional capacity is the cornerstone of intelligent programming. By systematically applying the principles of static versus dynamic screening, assessing the core's crucial role in stability, and utilizing objective testing, you can accurately define functional ability in every client. This detailed understanding allows you to design highly specific corrective and performance-based programs. Moving from subjective observation to objective data ensures your functional movement and performance training is safe, precise, and maximally effective. To manage complex assessment data, track client progress, and seamlessly integrate correctives into your training schedules, coaches need the best crm for personal trainers to keep everything organized. FitBudd offers the digital tools necessary to streamline your assessment process and turn functional insights into long-term results.

%20to%20Become%20a%20Certified%20Personal%20Trainer-min.jpg)