Most athletes train to get faster, but fewer focus on decelerating, and that’s where most injuries occur.

Learning to slow down, absorb force, and control your body's ability during movement is the foundation of deceleration training. If you’ve ever wondered “What is a deceleration?”, it simply refers to the ability to reduce speed safely without losing form. In sports, this matters just as much as accelerating.

Many people use terms like deceleration or even ask how to define decelerated, but the goal is the same: teaching the body to stop efficiently. Through targeted deceleration exercises and sport-specific deceleration drills, athletes make progress in improving stability, balance, and force control during landings, cuts, and quick directional changes.

When you can decelerate with confidence, you move faster, reduce injury risk, and perform every athletic task with more power and precision. Let’s break it down.

What Is Deceleration?

To put it simply, deceleration is the act of slowing down your body safely and under control. In sports, it’s the moment an athlete reduces speed, absorbs force, and prepares for the next movement, whether that means changing direction, stopping suddenly, or landing from a jump. When coaches explain “What is a deceleration?”, they’re talking about how efficiently an athlete can manage momentum.

The term, deaccleration, simply means controlling speed by using proper mechanics and muscular strength. Deceleration isn’t passive; it requires the body to produce high levels of eccentric force to prevent the knees, hips, and ankles from collapsing under pressure.

Because so many injuries happen during poor stopping mechanics, athletes must learn decelerating skills through structured deceleration exercises and deceleration drills that target stability, balance, and force absorption.

Ready to dive deeper?

Why Deceleration Matters

When you sprint, jump, or react in sports, your body creates high levels of momentum. Deceleration training teaches the muscles, especially the quads, hamstrings, glutes, and calves, to handle that momentum safely.

Every cut, landing, stop, and quick redirection depends on your ability to decelerate efficiently. Poor technique often leads to knee collapse, ankle instability, awkward landings, and increased injury risk.

How the Body Decelerates in Motion

Decelerating is a coordinated action involving:

- Eccentric muscle contractions

- Hip, knee, and ankle alignment

- Foot placement and ground contact

- Stability through the core and upper body

- The ability to absorb force through one leg or two legs

Where Deceleration Shows Up in Sports

Deceleration is present in almost every athletic movement, including:

- Stopping after sprinting

- Slowing down before changing direction

- Landing from jumps

- Preparing for a cut or pivot

- Breaking momentum in multi-directional drills

- Reacting in chaotic, game-like situations

Training Deceleration Properly

The goal of deceleration training is to build an athlete’s ability to stop quickly, safely, and repeatedly under different conditions. This includes strength work in the weight room , plyometrics, and sport-specific deceleration drills that improve force absorption and body control.

Common deceleration exercises include:

- Tempo squats

- Eccentric lunges

- Step-down variations

- Landing mechanics drills

- Single-leg stability exercises

Why Deceleration Matters for Athletes

Most athletes spend hours improving acceleration, sprint mechanics, and explosive power, but the real difference between average movers and elite performers is their ability to decelerate. When your body can slow down quickly, absorb force, and stabilize under pressure, whether it’s a ball or an opponent, everything becomes safer, smoother, and faster.

In sport, almost every explosive action begins with a controlled stop. Before an athlete can redirect, pivot, or accelerate again, they must pass through a phase of decelerating. This is where deceleration training, deceleration exercises, and deceleration drills become essential.

Without trained eccentric strength and proper mechanics, the joints, not the muscles, end up absorbing the impact. That’s where most injuries occur.

Why Deceleration Is So Critical in Sports

Here’s why coaches place such a high emphasis on deceleration:

- Up to 70% of non-contact ACL injuries happen during poor deceleration, not jumping or sprinting.

- Most cutting and agility movements require efficient force absorption before the athlete re-accelerates.

- Athletes with stronger deceleration control show significantly better change-of-direction ability.

- Proper stopping mechanics reduce stress on the knee, ankle, hip, and lower back.

The Performance Advantage

Deceleration doesn’t just prevent injury but also boosts performance:

- Better brakes = better acceleration. When you control the eccentric phase, you create more elastic energy for the next movement.

- Greater balance and stability when landing on one foot or reacting to fast changes.

- Improved agility, because athletes can lower their center of mass and change direction faster.

- Cleaner technique during pivots, jumps, shuffles, and multi-directional transitions.

In simple terms: if an athlete can’t decelerate efficiently, they can’t accelerate powerfully.

Deceleration Is the Foundation of Every Movement Chain

Nearly every athletic sequence follows the same pattern:

- Accelerate

- Decelerate

- Change directions

- Accelerate again

The middle steps that most people skip in training are where games are won or lost. A weak deceleration phase ruins the entire chain.

The Science Behind Deceleration Training

To understand why deceleration training is so powerful for athletes, you need to look at what happens inside the body when you’re decelerating. Stopping your body quickly isn’t passive; it's a complex, high-force action where the muscles, joints, and nervous system work together to create stability and absorb force safely.

In fact, the forces experienced during rapid deceleration are often higher than the forces produced during acceleration or jumping.

The Eccentric Phase: Your Body’s Natural Braking System

At the center of deceleration is the eccentric phase, the part of a movement where the muscles lengthen under load. This is where the body controls speed, prevents the knee from collapsing, and distributes force across the leg muscles.

During the eccentric phase of decelerating:

- The quads control knee bending

- The hamstrings stabilize the tibia

- The glutes manage hip position and internal/external rotation

- The calves regulate foot and ankle stiffness

- The core keeps the trunk from falling forward

When these muscles don’t fire effectively, force goes straight to the joints, leading to injury.

Force Absorption: How the Body Handles Impact

Every time you land, cut, or slow down, your legs and feet must absorb force. This is known as force absorption, and it’s one of the most important components of deceleration mechanics.

Three things determine how well your body handles impact:

- Joint angles – lower center of mass = better force absorption

- Ground contact – proper foot placement improves stability

- Muscular tension – stronger eccentric contractions reduce joint stress

Good deceleration exercises train all three.

Neuromuscular Control: The Brain–Body Connection

Decelerating effectively isn’t just physical; it’s neurological. The nervous system must react instantly to changes in direction, surface, and momentum. High-level athletes can change direction in milliseconds because their neural pathways are trained to respond quickly.

Deceleration drills sharpen:

- Reaction time

- Movement sequencing

- Joint alignment

- Postural control

- Body awareness

This is why deceleration training dramatically improves agility and sport-specific movement.

Planes of Motion: Why Deceleration Happens Everywhere

Athletes don’t move in a straight line. They stop, turn, pivot, shuffle, and rotate through all three planes:

- Sagittal plane – forward/backward deceleration

- Frontal plane – lateral shuffling and stopping

- Transverse plane – rotational braking before cutting or turning

Many injuries occur when athletes attempt to decelerate in the frontal or transverse plane without enough stability or strength. Proper deceleration exercises build control across all three.

Load & External Forces

Decelerating under body weight is one thing, but elite athletes must also handle external load, awkward landings, sport equipment, unpredictable opponents, and game-speed forces. This increases the demand on muscles, tendons, and connective tissues.

Examples of external load during decelerating:

- Holding a medicine ball

- Catching unexpected momentum

- Landing with uneven foot pressure

- Cutting while fatigued

- Eccentric overload in the weight room

That’s why strength training and controlled deceleration drills are essential for long-term injury reduction.

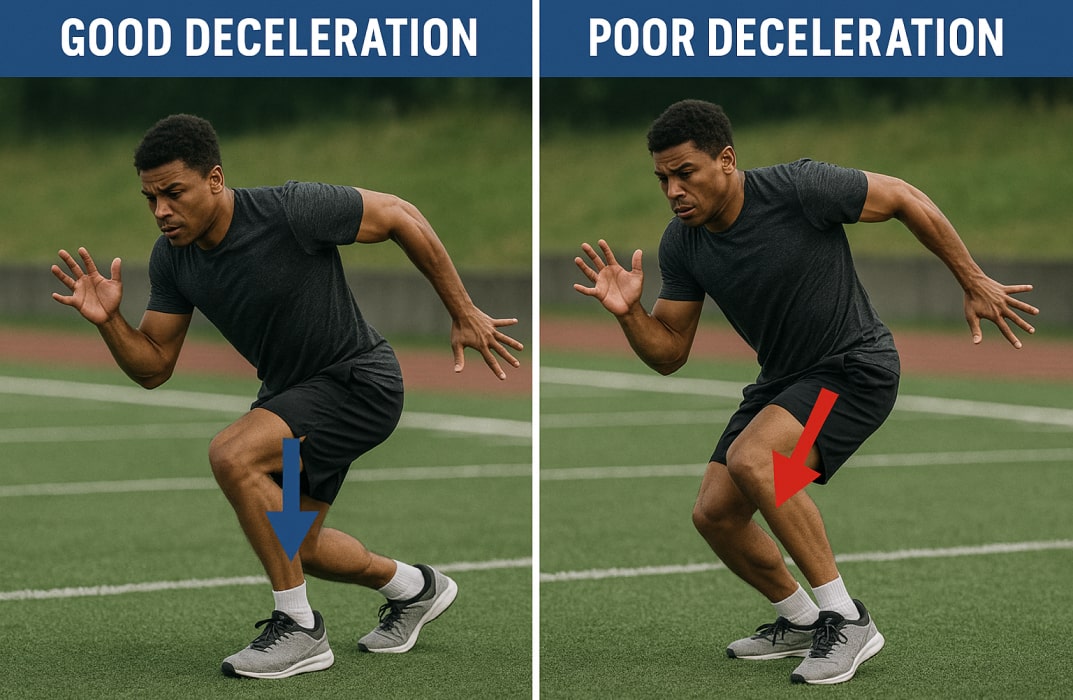

Deceleration Mechanics: How the Body Stops Safely

Decelerating may look simple from the outside, but internally it’s one of the most demanding athletic skills. When an athlete slows down, whether from a sprint, a jump, or a quick change of direction, the body must coordinate muscles, joints, foot placement, and posture to absorb force without losing balance. Understanding the mechanics behind deceleration helps athletes maintain a standing position while performing deceleration exercises and deceleration drills with better form and safer technique.

Lower-Body Mechanics: The First Line of Force Absorption

When decelerating, the lower body controls almost everything:

- Hips hinge to lower the center of mass, helping the body stabilize.

- Knees bend to increase force absorption and reduce joint stress.

- Ankles and feet manage ground contact, controlling how force travels upward.

- Leg muscles enter an eccentric contraction to slow momentum.

A well-timed hip hinge and knee bend allow the athlete to “sink” into the movement instead of collapsing or stopping stiffly.

Foot Placement & Ground Contact

Foot position determines how safely and efficiently the body slows down. Proper deceleration requires:

- The foot to land under the hips, not too far forward

- A mid-foot to forefoot strike, not heel-heavy braking

- Balanced pressure across both feet when decelerating with two legs

- Stability when landing on one foot during single-leg stops

Incorrect foot placement causes the knee to collapse inward or forces to travel unevenly through the leg, which are common patterns linked with ACL injuries.

Hip & Knee Alignment: Controlling Rotation

Deceleration involves a constant battle between internal rotation and external rotation at the hip. Strong hip stabilizers prevent the knees from caving in and help maintain alignment during sudden braking.

Good alignment includes:

- Knees tracking over the toes

- Hips staying level

- Core controlling trunk rotation

- Load is spread evenly through the leg muscles

Athletes who lack strength or stability in these areas rely too heavily on joints instead of muscles, increasing injury risk.

Upper-Body & Core Control

The upper body plays a significant role in decelerating safely. The core, trunk, and even the arms control momentum and help maintain balance when stopping or changing direction.

Key actions include:

- Neutral spine to avoid collapsing forward

- Arm position to maintain balance during rapid deceleration

- Strong trunk control to keep the body aligned while redirecting movement

Without core stability, the lower body has to compensate making deceleration inefficient and risky.

Center of Mass Management

Elite athletes stop smoothly because they keep their center of mass low and within their base of support. This means:

- Bending the hips and knees

- Keeping the chest slightly forward

- Maintaining balance between both legs or stabilizing on one leg

- Positioning the body so it’s ready to accelerate again

Managing the center of mass separates clean deceleration from unstable, sloppy stops.

How These Mechanics Work Together

A perfect deceleration sequence often looks like this:

- Foot contacts the ground under the hips

- Knees and hips bend to begin the eccentric phase

- Muscles absorb force and slow the body

- Core stabilizes to maintain posture

- Athlete “sticks” the landing or prepares to change directions

Every step here can be trained through targeted deceleration exercises and drills.

Benefits of Deceleration Training (Why It Matters)

Deceleration training is one of the most overlooked yet powerful methods for boosting performance and reducing injury risk. When you focus on decelerating effectively, your body learns to absorb force, control momentum, and stabilize joints under pressure.

This is exactly why deceleration exercises and deceleration drills are essential for athletes who sprint, jump, change direction, or stop suddenly in sports like football, basketball, tennis, and running.

If you’ve ever wondered “What is a deceleration?”, it simply means slowing down the body safely and under control. When you understand how to define decelerated movement, you quickly see that every landing, cut, or sudden stop depends on this skill.

Poor mechanics or confusion around terms like deacceleration or deaccleration often leads to knee collapse, ankle rolling, or muscle strains.

By integrating structured deceleration training, athletes build stronger tendons, sharper neuromuscular control, better balance, and improved agility, giving them a measurable advantage in performance while dramatically lowering injury risk.

Key Muscles Used in Deceleration (Your Body’s Built-In Braking System)

When an athlete is decelerating, it’s not just one muscle doing the work; it’s a coordinated team effort. Understanding which muscles handle force absorption helps you perform deceleration exercises, deceleration drills, and full deceleration training with better form and safer mechanics.

If you’ve ever wondered “What is a deceleration?”, it’s the moment these muscles fire eccentrically to control motion. Even if someone types deacceleration or deaccleration, the body still relies on the same muscular system to define decelerated movement.

Quadriceps: Primary Brakes for the Knee

The quads handle a huge portion of the eccentric load during landing and stopping. When you slow down, they prevent the knee from collapsing and help you absorb force smoothly.

Hamstrings: Protectors of the Knee

The hamstrings stabilize the tibia, especially during rapid deceleration or change of direction. Weak hamstrings often lead to knee instability, one of the biggest risk factors for ACL injuries.

Glutes: Hip Stabilizers and Direction Controllers

The glutes control hip extension, internal rotation, and external rotation during decelerating. They keep the hips level and allow the legs to handle force without collapsing inward.

Calves & Ankle Stabilizers: Ground-Contact Managers

Every deceleration starts at the foot. The calves stabilize the ankle and regulate how force transfers upward. Poor ankle control ruins the entire deceleration chain.

Core & Trunk Muscles: Balance and Alignment

Your core controls posture, keeps the spine neutral, and prevents excessive forward lean. Without strong trunk stability, the legs lose efficiency, and force absorption becomes dangerous.

Upper-Body Stabilizers (Including Teres Minor)

Even the upper body matters. Muscles like the teres minor help control arm movement and rotational forces during cutting, landing, or reacting to sudden changes in direction.

Deceleration Mechanics Across Planes of Motion

Every athlete decelerates in more than one direction. Whether you're landing, stopping, or preparing to change direction, your body isn’t just slowing down in a straight lineit’s reacting across the sagittal plane, frontal plane, and transverse plane all at once.

This is why understanding what is a deceleration in different movement patterns is essential for safe, efficient performance. Even if someone mistakenly types deacceleration or deaccleration, the fundamentals remain the same: the body must absorb force, stabilize, and regain control to define decelerated motion.

Deceleration in the Sagittal Plane (Forward–Backward Control)

This is the most familiar type of decelerating, slowing down while running, landing from a jump, or coming to a controlled stop.

Key mechanics include:

- Soft landing on the foot

- Hips and knees bend to absorb force

- The trunk stays aligned with the direction of motion

Many foundational deceleration exercises and basic deceleration drills start here to build safe eccentric control.

Deceleration in the Frontal Plane (Side-to-Side Movement)

Athletes constantly shift side to side during sports like tennis, basketball, and football.

Key mechanics include:

- Stabilizing on one foot before changing direction

- Using the opposite leg to brake lateral motion

- Keeping knees aligned to reduce injury risk

Poor frontal-plane control is one of the biggest contributors to knee valgus and ankle sprains, which is why deceleration training must include lateral drills.

Deceleration in the Transverse Plane (Rotational Braking)

This is the most challenging plane because rotational forces are harder to manage.

Key mechanics include:

- Controlling hip internal rotation and external rotation

- Proper arm action for balance

- Stopping rotation before reaccelerating or changing direction

Rotational deceleration is often where athletes lose form, making sport-specific deceleration drills essential. This includes pivot stops, rotational landings, and multi-directional agility work.

Why Multi-Plane Deceleration Matters

Real-world sports never stick to one direction. Athletes must be able to:

- Stop forward momentum

- Absorb lateral force

- Control rotational motion

- Change direction instantly

This is why high-level performance and injury prevention depend on training decelerating across all planes, not just practicing basic stops.

Common Mistakes Athletes Make When Decelerating

Even when athletes understand what is a deceleration, many still struggle with proper technique. Decelerating is a learned skill, and most breakdowns happen because the athlete has never developed the ability to define decelerated movement under speed or fatigue.

These mistakes show up constantly during deceleration training, deceleration exercises, and deceleration drills, and they’re often the reason injuries happen, regardless of whether someone spells it deceleration, deacceleration, or deaccleration.

Below is a clear table showing the most common deceleration mistakes, why they happen, and how to fix them.

Quick comparison: Deceleration Mistakes & How to Fix Them

Why Fixing These Mistakes Matters

Once athletes clean up these patterns, deceleration training becomes safer and far more effective. Better mechanics mean:

- Stronger joints

- Better force absorption

- Faster change of direction

- Less stress on knees and ankles

- More control under game-speed conditions

Correcting these mistakes is one of the fastest ways to improve athletic performance.

Deceleration Training vs Acceleration Training

Acceleration gets all the attention everyone wants to run faster, jump higher, and explode out of a cut. But athletes quickly learn that performance isn’t only about how fast you can go; it’s about how fast you can slow down. That’s where decelerating becomes just as important as accelerating.

To understand the difference, you need to be clear on what is a deceleration. It simply means reducing speed under control by absorbing force through the muscles. Even if someone writes it as deacceleration or deaccleration, the meaning doesn’t change.

When you define decelerated movement, you’re talking about the moment your muscles work eccentrically to stop the body safely.

Acceleration training focuses on producing force driving the legs, pushing the ground away, and building momentum. Deceleration training focuses on absorbing that force, lowering your center of mass, positioning your foot correctly, and controlling motion before the next step.

The two skills are connected. Without strong deceleration mechanics, an athlete can’t accelerate effectively out of a cut, a turn, or a landing. Poor braking makes every movement slower, less efficient, and far riskier. This is why elite training programs combine acceleration work with deceleration exercises and deceleration drills to build a complete, resilient athlete.

When you train both, your movement becomes smoother, quicker, and much safer because speed doesn’t matter if you can’t stop.

Best Deceleration Exercises (Detailed Guide)

If you truly want to get better at decelerating, you need to train it directly. Strength alone isn’t enough. The body must learn how to absorb force, control momentum, and maintain proper alignment at high speeds. That’s why the best deceleration exercises blend strength, stability, footwork, and eccentric control. These movements teach your body how to handle precisely what happens during sport, stopping, landing, cutting, and reacting.

Before diving in, remember: whether you call it deceleration, deacceleration, or deaccleration, the goal is the same: teaching your body how to define decelerated motion with precision and confidence.

Foundational Deceleration Exercises (Build the Base)

These movements teach your body fundamental braking mechanics. They’re perfect for beginners or anyone new to structured deceleration training.

• Tempo Squats (5–6 second lowering)

Great for improving eccentric strength and helping the body practice controlled force absorption.

• Split-Squat Eccentrics

This teaches hip stability, knee alignment, and how the legs should behave when decelerating on one side.

• Step-Downs and Box Reaches

A simple but highly effective drill to improve single-leg control and stable foot contact.

Plyometric Deceleration Exercises (Landing Mechanics)

Once foundational control is solid, athletes progress to landing-focused movements.

• Snap-Downs

A fast “drop” into a stable position, teaching athletes how to stop movement quickly.

• Box Drop to Stick Landing

Step off a box, land softly, and hold the position. Great for practicing how to control momentum.

• Broad Jump → Stick

Jump forward and freeze at the landing. This improves eccentric control and trunk stability.

Single-Leg Deceleration Exercises (Sport-Specific Braking)

Most real-world decelerating happens on one foot. These exercises help you build the strength and balance needed to stop confidently.

• Single-Leg Stick Landings

Land on one foot and “stick” the position. Teaches control and alignment.

• Lateral Bound to Single-Leg Stick

Perfect for building braking power in the frontal plane.

• Single-Leg RDL (Eccentric Focus)

Improves hamstring and glute control, crucial for stability during directional changes.

Strength-Based Deceleration Training (Weight Room Power)

Strength training plays a major role in deceleration because strong muscles absorb more force.

• Eccentric Leg Press (Slow Lowering)

Builds high levels of controlled braking force.

• Romanian Deadlifts (3–4 second descent)

Strengthens the posterior chain, the engine of every decelerated movement.

• Lunge With Eccentric Drop

Step forward, “catch” the bodyweight, and lower slowly while controlling knee alignment.

Medicine Ball Deceleration Drills (Dynamic Braking)

Medicine ball work adds load, rotation, and unpredictability just like sports.

• MB Drop → Catch

Decelerate the ball’s momentum, teaching total-body force absorption.

• Rotational MB Toss → Stick

Throw, rotate, stop, and hold the landing is ideal for athletes who cut or pivot often.

• Overhead MB Reverse Lunge (Eccentric Focus)

Strengthens trunk stability and teaches controlled braking under external load.

Real-World Deceleration Drills (On-Field Application)

Now we take everything above and blend it into sport-like speed.

• Sprint → Stick

Run fast, stop quickly, and freeze. Great for building timing and body control.

• Shuffle → Plant → Change Direction

Mimics in-game lateral movement with real-time foot placement.

• 45° and 90° Plant Drills

Teaches athletes how to decelerate at angles they actually experience in competition.

These deceleration exercises and deceleration drills form the backbone of safe, powerful deceleration training. They build the braking strength and control athletes need before adding speed or complexity.

Rapid Deceleration & Change of Direction Mechanics

Rapid deceleration is the heart of change-of-direction performance. Before an athlete can cut, turn, or explode into a new line of movement, they must first slow down efficiently. This is where many athletes fall apart, not because they lack speed, but because they don’t know how to define decelerated motion at game speed.

To understand rapid stopping, it helps to revisit what is a deceleration: the controlled reduction of speed by absorbing force through the lower body and trunk. Even when people spell it as deacceleration or deaccleration, the science is the same your body must decelerate cleanly before you can safely change direction.

Good change-of-direction mechanics require three key components:

Proper Footwork: One Foot, Opposite Foot, Opposite Leg Control

Most decelerating starts with one foot hitting the ground under the athlete’s center of mass. From there:

- The opposite foot helps stabilize the landing.

- The opposite leg creates a braking force to control momentum.

- The hips guide which way the athlete can push off next.

Poor foot placement slows the athlete down and increases knee/ankle stress.

Hip & Knee Mechanics: Internal and External Rotation

High-level change of direction requires clean rotational control.

Key actions include:

- Hip internal rotation to absorb force when slowing down

- Hip external rotation to push off and redirect the body

- Knee alignment over the toes during deceleration

- Stable trunk to prevent unnecessary rotation

If these mechanics break down, the athlete loses speed and increases injury risk.

Lowering the Center of Mass: The Secret to Sharp Cuts

Athletes who stay tall when decelerating struggle to stop quickly.

Proper technique includes:

- Dropping the hips

- Bending the knees

- Staying balanced over the feet

- Keeping the chest slightly forward

This lets the body absorb force efficiently and prepares you to re-accelerate instantly.

Force Absorption Before Redirection

You cannot change direction until the body has fully absorbed force.

This is often overlooked during deceleration training, but it’s what separates smooth movers from sloppy ones.

Sharp changes of direction require:

- Strong eccentric braking

- Stable single-leg control

- The ability to stop momentum fully

- Quick repositioning of the foot for the new direction

Athletes who cheat this step rely on joints instead of muscles, leading to common injuries during fast COD movements.

Deceleration Drills That Improve Change of Direction

These sport-specific deceleration drills teach the body how to blend braking and re-acceleration fluidly:

- Sprint → Plant → Cut (45° or 90°)

- Lateral Shuffle → Stick → Push Off

- Sprint → Hard Stop → Re-Accelerate

- Crossover Step → Decelerate → Redirect

Each drill reinforces how decelerating sets up the next movement.

Deceleration Drills for Different Sports

Every sport demands decelerating in different ways. A basketball player stops differently from a footballer. A tennis athlete breaks differently than a sprinter. Understanding what is a deceleration in each sport helps coaches choose the right deceleration exercises and deceleration drills so athletes can slow down safely, redirect movement, and reduce injury risk.

Even if someone types deacceleration or deaccleration, the fundamentals stay the same each sport requires the ability to define decelerated movement under unique angles, speeds, and loads. That’s why sport-specific deceleration training is essential.

Below is a clear breakdown showing which type of drill best suits each sport.

Best Deceleration Drills for Each Sport

How These Drills Improve Performance

Regardless of the sport, these drills reinforce the same four principles:

- Absorbing force through the legs and trunk

- Positioning one foot or the opposite leg correctly before redirecting

- Controlling momentum instead of letting the body fold

- Building consistent, clean mechanics so athletes stay balanced

When performed consistently, these deceleration drills upgrade an athlete’s braking ability, reaction speed, and change-of-direction power while dramatically reducing injury risk.

How to Progress Deceleration Training Safely (Beginner → Advanced)

Decelerating is a skill, and like any skill, it needs smart, structured progression. Too many athletes jump straight into high-speed cutting and intense deceleration drills without first learning the basics. This is where injuries happen.

Whether you’re coaching beginners or advanced players, progressing deceleration training step-by-step ensures the body learns how to slow down, stabilize, and define decelerated movement without overload.

Before building speed, you must build control. This progression model moves athletes from simple deceleration exercises to game-speed deceleration demands, regardless of how someone spells it (deceleration, deacceleration, or deaccleration).

Beginner Progression: Learn the Fundamentals

The first phase focuses on slow, controlled movements. The goal is to understand what is a deceleration and teach the body how to absorb force without losing balance.

Beginner exercises include:

- Slow eccentric squats

- Step-downs from low boxes

- Split-squat eccentrics

- Basic stick landings (two legs → one foot)

Training focus:

- Foot placement

- Knee alignment

- Soft landing mechanics

- Stable trunk position

Intermediate Progression: Add Speed & Single-Leg Control

Once the basics feel clean, athletes move into moderate-speed decelerating with more dynamic actions.

Intermediate exercises include:

- Lateral bounds → stick

- Single-leg snap downs

- Moderate-speed sprint → stick

- 45° and 90° plant drills

Training focus:

- Strong single-leg control

- Faster braking

- Proper hip internal/external rotation

- Smooth transition into new directions

Advanced Progression: Game-Speed Deceleration

The final phase prepares athletes for real-world movementhigh velocity, fast reactions, awkward angles, and unpredictable motion.

Advanced drills include:

- High-speed sprint → rapid deceleration

- Reactive change-of-direction drills

- Multi-step COD sequences

- Rotational decel → accelerate patterns

Training focus:

- Absorbing force at high velocity

- Quick transitions after braking

- Staying balanced during chaotic movement

- Preparing the body for sport-specific demands

Why This Progression Matters

Athletes who skip progression often develop poor habits that are hard to fixlike stiff landings, knee collapse, or weak foot control. Proper progression helps the body adapt safely so deceleration becomes automatic, powerful, and efficient.

Smart progression ensures:

- Better braking mechanics

- Improved force absorption

- Safer high-speed movement

- Stronger performance in any sport

Final Thoughts

At its core, athletic performance isn’t just about how fast you can go, it’s about how well you can slow down. Whether you’re sprinting, jumping, or changing direction, every powerful movement has a braking phase. And the athletes who master decelerating are the ones who move smoothly, react more quickly, and stay injury-free for longer.

Understanding what a deceleration is helps you appreciate how important it is to control momentum, absorb force, and keep the body aligned under speed. Even if people spell it as deacceleration or deaccleration, the science behind it stays the same: you must teach your body how to brake just as deliberately as you teach it to accelerate. When you learn to define decelerated movement, you unlock a completely different level of control.

With the right mix of deceleration exercises, structured strength work, and targeted deceleration drills, athletes build better stability, stronger joints, and more efficient movement patterns. This is what true deceleration training delivers, not just better braking, but better performance overall.

No matter your sport, age, or skill level, mastering deceleration is one of the smartest investments you can make. Because great athletes don’t just move fast, they stop fast, too.

.jpg)

%20to%20Become%20a%20Certified%20Personal%20Trainer-min.jpg)